Navigating the Article

Let's be honest, a toothache that turns into a full-blown, throbbing pain with swelling is one of the worst feelings. You're sitting there, Googling frantically, trying to figure out what's happening in your mouth. Is it a cavity gone bad? Is it your gums? The terms you keep seeing are "periapical abscess" and "periodontal abscess." They sound similar, and honestly, the pain might feel similar too, but I can tell you from talking to dentists and reading more studies than I care to admit, they're completely different beasts.

Getting them mixed up isn't just a technical error. It can lead to the wrong treatment, which means the pain might not go away, or worse, the problem could come roaring back. So let's cut through the confusion. This isn't a dry textbook chapter. Think of it as a chat with someone who's been down the research rabbit hole so you don't have to.

The Core Difference in One Line: A periapical abscess starts from a dead or dying tooth nerve (the pulp), while a periodontal abscess starts from an infection in the gums and bone supporting a (usually) live tooth. Origin story matters.

Where Does the Trouble Begin? The Root of the Problem

You can't understand the fight between a periapical abscess and a periodontal abscess without knowing where they come from. The starting point explains everything that comes after.

Periapical Abscess: The Tooth's Inner Crisis

Picture your tooth. The hard white shell is the enamel. Inside that is dentin. And deep in the center is the pulp chamber—a little room housing nerves, blood vessels, and connective tissue. That's the tooth's lifeline.

A periapical abscess happens when that inner sanctum gets invaded and dies. How?

- Deep Decay: This is the classic villain. A cavity that's ignored drills its way through enamel and dentin until it hits the pulp. Bacteria throw a party in the nerve, leading to infection, inflammation, and eventually, the death of the pulp tissue (what dentists call "pulp necrosis").

- A Cracked or Broken Tooth: A big chip or a hairline crack from an injury or chewing something hard can give bacteria a direct highway to the pulp.

- Failed Old Dental Work: Sometimes, a large old filling or a crown can leak over time, letting bacteria sneak in underneath.

The key thing here is the pulp is dead or dying. The infection, with nowhere else to go, burrows out through the tiny opening at the very tip of the tooth root (the "apex"). That's the "periapex"—hence the name periapical abscess. It forms a pus-filled pocket in the jawbone around the root tip. Ouch.

I remember a friend who had a huge old silver filling. For years it was fine, then one day, boom—excruciating pain. Turns out, decay had been brewing under that filling for ages, finally reaching the nerve. Classic periapical abscess scenario. The delay in getting it checked cost him a root canal instead of a simpler filling.

Periodontal Abscess: The Gum's Rebellion

Now, this one is a gum disease story. Your tooth isn't just sitting in the bone like a fence post in concrete. It's held by a sophisticated system of gums, a ligament, and bone—the periodontium.

A periodontal abscess is a localized, walled-off infection in the tissues *beside* the tooth root, not at the tip. The tooth's nerve is usually perfectly alive and healthy (which changes the pain quality, as we'll see). This abscess is almost always a complication of pre-existing periodontitis, which is advanced gum disease.

Here's how it unfolds:

- Plaque and tartar build up, causing chronic gum inflammation (gingivitis, then periodontitis).

- The gums pull away from the tooth, forming deep pockets.

- Bacteria thrive in these deep, dirty pockets.

- Something happens to block the pocket's opening. Maybe a piece of popcorn husk gets shoved deep inside, or the gum tissue swells over the entrance. The bacteria get trapped inside with no drainage.

- The infection builds up rapidly in the confined space of the pocket, forming an abscess in the gum and supporting bone, right next to the tooth root.

It can also happen after a dental procedure if a bit of debris is forced into a gum pocket. The point is, the tooth itself—its inner nerve—is often an innocent bystander in a periodontal abscess. The problem is outside the tooth.

See the divergence already? One is a tooth problem that spreads to the bone. The other is a gum/bone problem that menaces a tooth. This fundamental difference between a periapical abscess and a periodontal abscess dictates everything—how it feels, how it's spotted, and crucially, how it's fixed.

Feeling the Difference: Symptoms and Signs

Both can hurt like crazy. But if you listen closely to your body (and I know it's hard when you're in pain), the symptoms whisper different stories.

Symptom Clues at a Glance

Periapical Abscess Tends To: Have severe, lingering, throbbing pain. The tooth often feels "high" or sensitive to biting. You'll likely have a history of toothache or sensitivity to hot/cold that suddenly stopped (the nerve died). The swelling is often closer to the root tip, so it may appear as a gum boil (fistula) nearer to the tooth apex or even cause facial swelling.

Periodontal Abscess Tends To: Have deep, gnawing pain that's more localized to the gum area. The tooth is often sore to touch *from the side* and may feel loose. The gums around it are red, shiny, and swollen, and you can usually press on the gum and see pus ooze from the pocket. The tooth often still reacts to temperature tests because the nerve is alive.

Here's a more detailed breakdown. A periapical abscess often gives you that classic "need to see a dentist NOW" pain. It's spontaneous, throbs in time with your heartbeat, and can be made worse by lying down (increased blood pressure to the area). The tooth itself is usually exquisitely tender to tap. You might have had a cavity or a large filling in that tooth.

With a periodontal abscess, the pain might be slightly less intense initially, but it's a deep, constant ache. The most telling sign is the gum. There's a red, swollen, balloon-like area on the gum next to the tooth. If you gently press it, pus might come out. The tooth often has noticeable gum recession, tartar buildup, and might wiggle a bit. Bad breath and a foul taste are very common.

Important: These are general guides. Symptoms can overlap. A long-standing periapical abscess might drain through the gum and look like a gum problem. A severe periodontal abscess can become incredibly painful. Never use this list to self-diagnose. Its purpose is to help you have a more informed conversation with your dentist.

How Your Dentist Tells Them Apart: The Diagnostic Detective Work

This is where the rubber meets the road. When you're in the chair, your dentist isn't guessing. They're collecting clues. I've always found this process fascinating—it's like dental forensics.

The Initial Exam: Asking and Looking

They'll ask about your pain history. That story of hot/cold sensitivity that vanished? Huge red flag for a dead nerve and a potential periapical abscess. They'll visually check for cavities, cracks, old restorations, and the state of your gums—looking for redness, swelling, and deep pockets.

The Vitality Test: Is the Tooth Alive?

This is a critical, simple test. The dentist might apply a very cold stimulus (like a frozen Q-tip) or a mild electric pulse to the tooth. If you feel a sharp, quick sensation that fades, the nerve is alive. If you feel nothing, the nerve is dead (necrotic). A dead nerve strongly points toward a periapical abscess. A live nerve points away from it and toward a periodontal abscess or other issue.

The Percussion Test: Tapping for Tenderness

A gentle tap on the tooth with a tool. Sharp pain on biting down directly on the tooth crown often suggests a periapical abscess, as the inflammation is at the root tip. Pain when tapping on the tooth *from the side* (on its cheek or tongue surface) is more indicative of a periodontal abscess, as the inflammation is in the ligament on the side of the root.

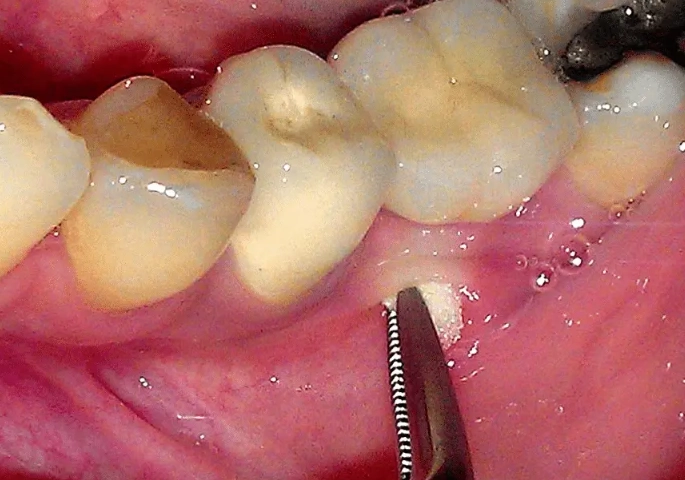

The Probing Exam: Measuring Gum Pockets

The dentist uses a tiny ruler (probe) to gently measure the space between your gum and tooth. Deep pockets (over 4mm), especially isolated ones with bleeding and pus, are the hallmark of periodontal disease and a likely site for a periodontal abscess.

The Definitive Evidence: Dental X-Rays

The X-ray is the smoking gun. It shows what's happening beneath the surface.

- Periapical Abscess X-ray: Shows a dark, rounded area (radiolucency) at the very tip of the tooth root. It's like a little shadow in the bone right at the end of the root. The tooth may also show a large cavity or a deep filling close to the pulp.

- Periodontal Abscess X-ray: Shows bone loss *down the side* of the tooth root, not at the tip. You might see a crater-shaped loss of bone. The dark area follows the contour of the root. The bone level around neighboring teeth is often also reduced.

Sometimes, especially with long-term infections, the picture gets muddy. But a good clinician puts all these pieces together—symptoms, tests, and X-rays—to make the call. The American Dental Association's resources on oral health conditions emphasize the importance of this comprehensive diagnostic approach to ensure correct treatment.

Let's put this side-by-side in a table. I find this helps cement the distinctions.

| Feature | Periapical Abscess | Periodontal Abscess |

|---|---|---|

| Origin / Cause | Infection of the tooth pulp (nerve), usually from deep decay, trauma, or a crack. The pulp is necrotic (dead). | Infection in the gum pocket and supporting bone (periodontium), usually from advanced gum disease where a pocket becomes blocked. |

| Tooth Vitality | Tooth is non-vital (does not respond to cold/electrical tests). | Tooth is usually vital (responds normally to vitality tests). |

| Primary Pain Location | Pain seems to come from the tooth itself. Severe, throbbing, often worse when lying down. | Pain is localized to the gums around the tooth. Deep, gnawing, constant ache. |

| Response to Tapping | Extremely tender to tapping directly on the biting surface. | More tender to tapping on the side of the tooth (lateral percussion). |

| Gum Appearance | Gums may appear normal, or have a "gum boil" (sinus tract) near the root tip. Swelling can be more diffuse and facial. | Localized, red, swollen, shiny gum bulge (parulis) next to the tooth. Pus often expressible from the gum pocket. |

| Tooth Mobility | Tooth is usually not loose initially (unless infection is very severe and chronic). | Tooth is often mobile (loose) due to underlying bone loss. |

| X-ray Findings | Dark area (radiolucency) at the tip of the root (periapical lesion). | Bone loss down the side of the root (vertical bone defect). Normal bone at root tip. |

| Common Patient History | History of toothache, large filling, or trauma to the tooth. | History of gum disease, bleeding gums, bad breath, and possibly recent food impaction. |

The Road to Relief: Treatment Paths Diverge

This is the most important part. Getting the diagnosis wrong here leads to the wrong fix, and the problem persists. It's frustrating for everyone.

Treating a Periapical Abscess

The goal is to remove the source of the infection: the dead, infected pulp tissue inside the tooth. The tooth structure itself can often be saved.

Root Canal Treatment (RCT) is the standard, tooth-saving procedure. The dentist or endodontist (root canal specialist):

- Makes a small opening in the top of the tooth.

- Removes all the dead nerve tissue, bacteria, and debris from the pulp chamber and root canals.

- Cleans, disinfects, and shapes the canals.

- Fills and seals the empty canals with a rubber-like material.

- Places a filling or, more commonly, a crown on top to restore the tooth's strength.

Once the internal infection is gone, the bone around the root tip usually heals on its own over months. Antibiotics are generally not the first-line treatment unless there is significant spreading infection or fever. The ADA guidelines often stress that the definitive treatment is mechanical removal of the infection via RCT, not just antibiotics, which only temporarily suppress it.

If the tooth is too damaged (severe crack down the root, massive decay), extraction might be the only option. But a successful root canal can last a lifetime.

Treating a Periodontal Abscess

The goal here is to clean out the infected gum pocket and establish drainage. Since the tooth nerve is healthy, a root canal is NOT needed.

Emergency treatment involves drainage. The dentist will gently numb the area and make a small incision in the swollen gum to let the pus drain, providing immediate pain relief. They will then thoroughly clean out the deep pocket (this is called "debridement") using special tools to remove plaque, tartar, and bacteria from the root surface deep under the gum.

The real, long-term treatment is managing the underlying gum disease. The acute abscess is just a symptom of the chronic condition. After the emergency is handled, you'll need:

- Deep Cleaning (Scaling and Root Planing): A thorough cleaning of all tooth roots under the gums to remove calculus.

- Improved Oral Hygiene: This is non-negotiable. Proper brushing and flossing to keep pockets clean.

- Possible Surgery: For deep, persistent pockets, a periodontist (gum specialist) might recommend flap surgery to access and clean the area better, or procedures to regenerate lost bone. The American Academy of Periodontology provides detailed patient resources on these treatment pathways.

Antibiotics might be used adjunctively here too, but again, the mechanical cleaning is the cornerstone.

I think this is where people get frustrated. They get the abscess drained, feel better, and skip the follow-up deep cleaning. Then six months later, it's back. Treating a periodontal abscess isn't a one-time event; it's the start of managing a chronic condition. It's a commitment.

So, to hammer it home: Periapical abscess treatment focuses on the inside of the tooth (root canal). Periodontal abscess treatment focuses on the outside of the tooth and gums (deep cleaning and gum therapy). Completely different plays from the medical playbook.

Common Questions People Actually Ask

To prevent a Periapical Abscess: Maintain excellent oral hygiene to prevent cavities. See your dentist regularly so small cavities are caught and filled early, long before they reach the nerve. Wear a mouthguard during sports to prevent traumatic cracks.

To prevent a Periodontal Abscess: Meticulous daily cleaning (brushing AND flossing) to prevent gum disease. Regular professional cleanings to remove tartar you can't remove at home. If you have gum disease, commit to the recommended maintenance therapy (periodontal cleanings every 3-4 months).

The Final Takeaway: Why Getting It Right Matters

Understanding the battle of periapical abscess vs periodontal abscess isn't about dental trivia. It's about understanding your own health. It empowers you to ask the right questions when you're in pain: "Is the nerve alive?" "Is this coming from the tooth or the gum?" "Will I need a root canal or a deep cleaning?"

It also explains why sometimes a dentist might refer you to a specialist—an endodontist for the intricate work of a root canal, or a periodontist for deep gum therapy. They're playing different positions on the dental field.

If you take away one thing, let it be this: severe tooth or gum pain with swelling is a sign to see a dentist immediately. Don't try to self-diagnose between a periapical and periodontal abscess. But by knowing the landscape, you can be a more engaged partner in your care, which always leads to a better outcome.

The pain might feel the same, but the road to getting rid of it for good is completely different. Make sure you and your dentist are on the right one.

Leave a Reply